A Green Mountain Writers feature for those who missed our recent Monday Morning Poetry Session…

Robert Frost is often introduced as Vermont’s beloved poet laureate, a gentle observer of woods, stone walls, and snowy evenings. We recite his lines in school, quote him on calendars, and imagine him walking country lanes with a notebook in hand. Yet this soft public image hides a far more complex poet whose work carries emotional depth, psychological tension, and the unmistakable weight of lived tragedy.

For our Monday Morning Poetry session this week, we gathered to look beyond the all too familiar Frost and into the poet who continues to shape American literature in ways both subtle and profound. What follows is a summary of that conversation for those unable to join us, along with insights into Frost’s craft and the lessons he leaves for modern writers.

A Life That Shadowed the Work

To understand Frost’s poetry, one must begin with the losses that marked his life. Frost endured more than ordinary hardship. His father died when Robert was only eleven. His mother passed early as well, after a long decline. One sister spent her final years institutionalized. Frost and his wife Elinor lost four of their six children to illness, complications from childbirth, or suicide, and Elinor herself struggled with chronic illness until her death in 1938.

Yet Frost never wrote openly about these events. That silence is important. He did not turn his grief into confessional poetry. Instead, he transformed private sorrow into crafted scenes, symbolic landscapes, and characters who carry emotional weight without naming it directly.

This ability to submerge tragedy beneath plain language is one of Frost’s defining strengths. The poems feel clear and accessible, but they vibrate with tension under the surface. It is the tension between what is spoken and what is withheld that gives them power.

Frost believed poetry begins not with meter or rhyme, but with the tones of real speech. He called this “the sound of sense.” It is the natural rise and fall of a person talking, the emotional arc of ordinary sentences.

“Two Tramps in Mud Time” is generally considered one of Robert Frost’s autobiographical poems. The poem reflects Frost’s own feelings and experience through the speaker, who is often read as a Frost persona, engaged in chopping wood, a solitary, physical labor he personally valued.

The poem subtly reveals the speaker’s internal conflict, his proprietary instinct over the wood and his conflicted generosity, without explicitly naming the emotional struggle. This restraint allows the personal pain, loneliness, or loss behind the speaker’s protective stance to be felt through his actions and reflections rather than explicit statement

The Sound of Sense

What makes Frost unique is what he does with that natural voice. He places it inside strict metrical patterns. The result is a living line that seems effortless, as if someone is simply speaking, yet it pulses with rhythmic structure.

For example, a line from “Mending Wall” may sound casual, even conversational. But clap out the stresses, and you hear the heartbeat of blank verse underneath. It is this tension between natural speech and traditional form that makes Frost’s lines feel both grounded and elevated.

For poets today, this is a vital lesson. It is possible to write formally without sounding formal. The goal is not to imitate Frost’s meter, but to understand how he sets speech against structure to create energy in the line.

Landscape as Emotional Stage

Frost wrote often about farms, fields, woods, snow, and stone fences. But these natural elements are never mere scenery. They are psychological landscapes.

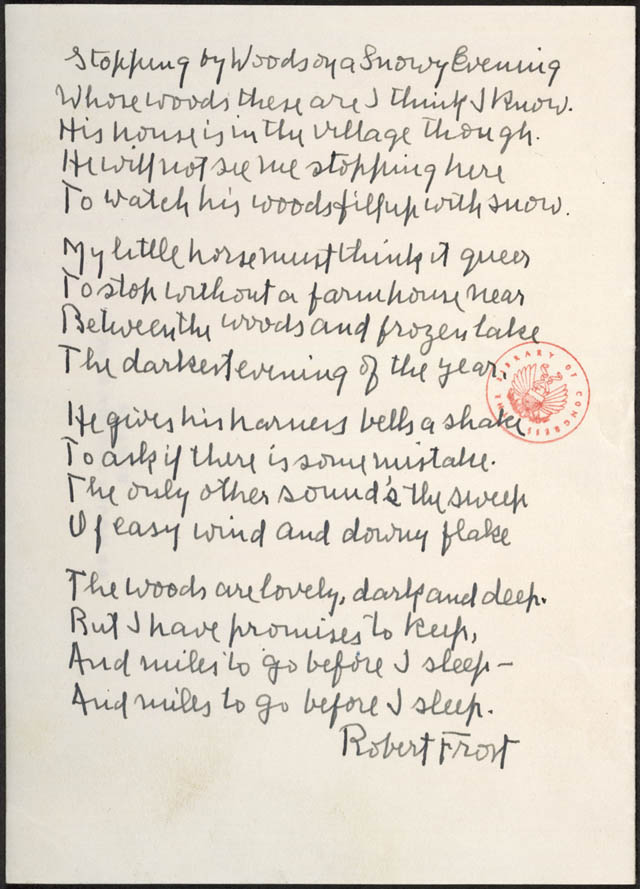

In “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” the quiet woods feel inviting, even enchanting, but something darker hums beneath the calm. The speaker lingers, pulled by stillness, but the poem ends with the reminder of “promises to keep.” The scene becomes a metaphor for hesitation, duty, and perhaps even mortality.

In “Out, Out,” the rural beauty of a Vermont afternoon heightens the shock of a sudden accident. After the tragedy, the poem concludes with the family turning back to their work because “life has to go on.” Frost allows the landscape itself to carry the weight of that realization.

“Birches” offers another striking example. The image of a boy swinging on ice-bent trees becomes a meditation on escape and return, on fantasy and responsibility. The natural world becomes a place where emotional conflict is staged, explored, and brought to the surface.

For poets, Frost’s use of place is an invitation. Choose landscapes that amplify emotion rather than merely decorate it.

Poems as Scenes, Not Diaries

Many of Frost’s greatest works function like small one-act plays. “Home Burial” stages a marriage in crisis. “The Death of the Hired Man” presents two characters wrestling with loyalty and responsibility. Even a quiet lyric like “Acquainted with the Night” suggests a deeply personal anguish without ever explaining it.

Frost trusted his readers. He left gaps for us to fill in. He allowed characters to contradict themselves, to withhold things, to speak in tones that reveal more than their actual words.

For contemporary poets, this restraint is liberating. We do not need to explain everything. Instead, we can present a moment of tension and let the reader follow the emotional thread.

Comfort and Dread Together

One of Frost’s most remarkable gifts is tonal ambiguity. His poems hold two feelings at once: comfort and unease, light and shadow, the familiar and the strange.

This is why Frost endures. His poems can be read by a child and enjoyed for their surface beauty, yet a seasoned reader recognizes the undercurrent of fear, sorrow, isolation, or longing beneath them.

The world in Frost’s poems is never simple. It is full of fragile boundaries and quiet ruptures. But it is also full of wonder.

What Frost Leaves to Modern Poets

During our discussion, we ended with five key takeaways:

- Begin with the tones of real speech.

- Let formal elements energize the line.

- Use landscape as a partner, not a backdrop.

- Build scenes instead of explaining feelings.

- Trust emotional ambiguity.

These principles help explain why Frost’s poems continue to resonate. They invite readers to return again and again, discovering new layers beneath the snow.

If you were unable to join us recently, we hope this deeper look at Frost inspires you to revisit his poems with fresh curiosity. His ability to craft clarity around complexity, and to hide profound emotion inside the simplest of lines, is a gift and a challenge to all writers.

In the 1920s, Frost lived part of the time in a colonial-era house in Shaftsbury, Vermont (the Stone House), and later at a nearby farm known as “The Gully,” both of which strengthened his ties to Vermont. In 1940, he bought the Homer Noble Farm (pictured left) near Ripton, Vermont, where he spent summers and falls until his death.